Charles Bell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Charles Bell (12 November 177428 April 1842) was a Scottish surgeon,

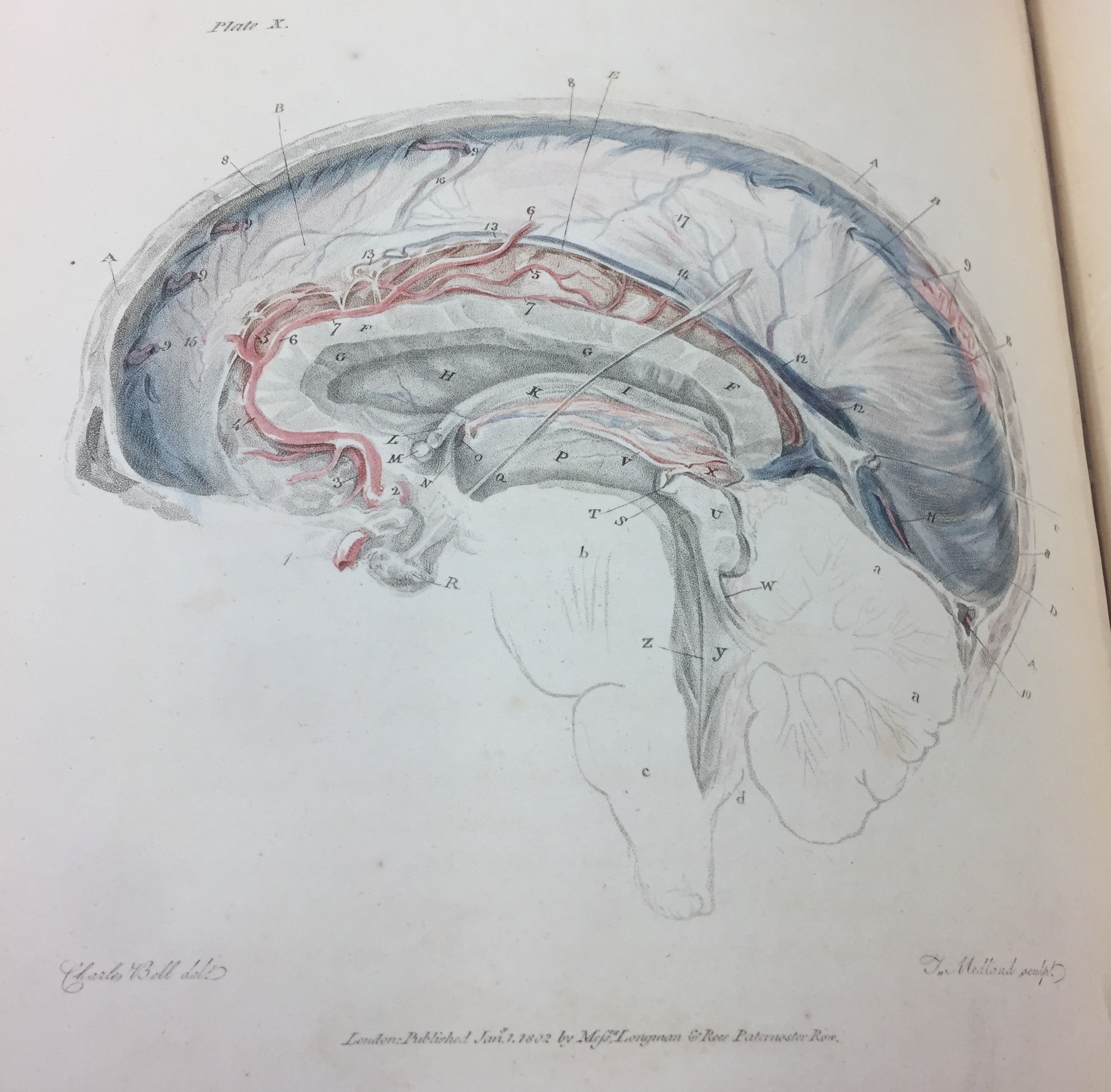

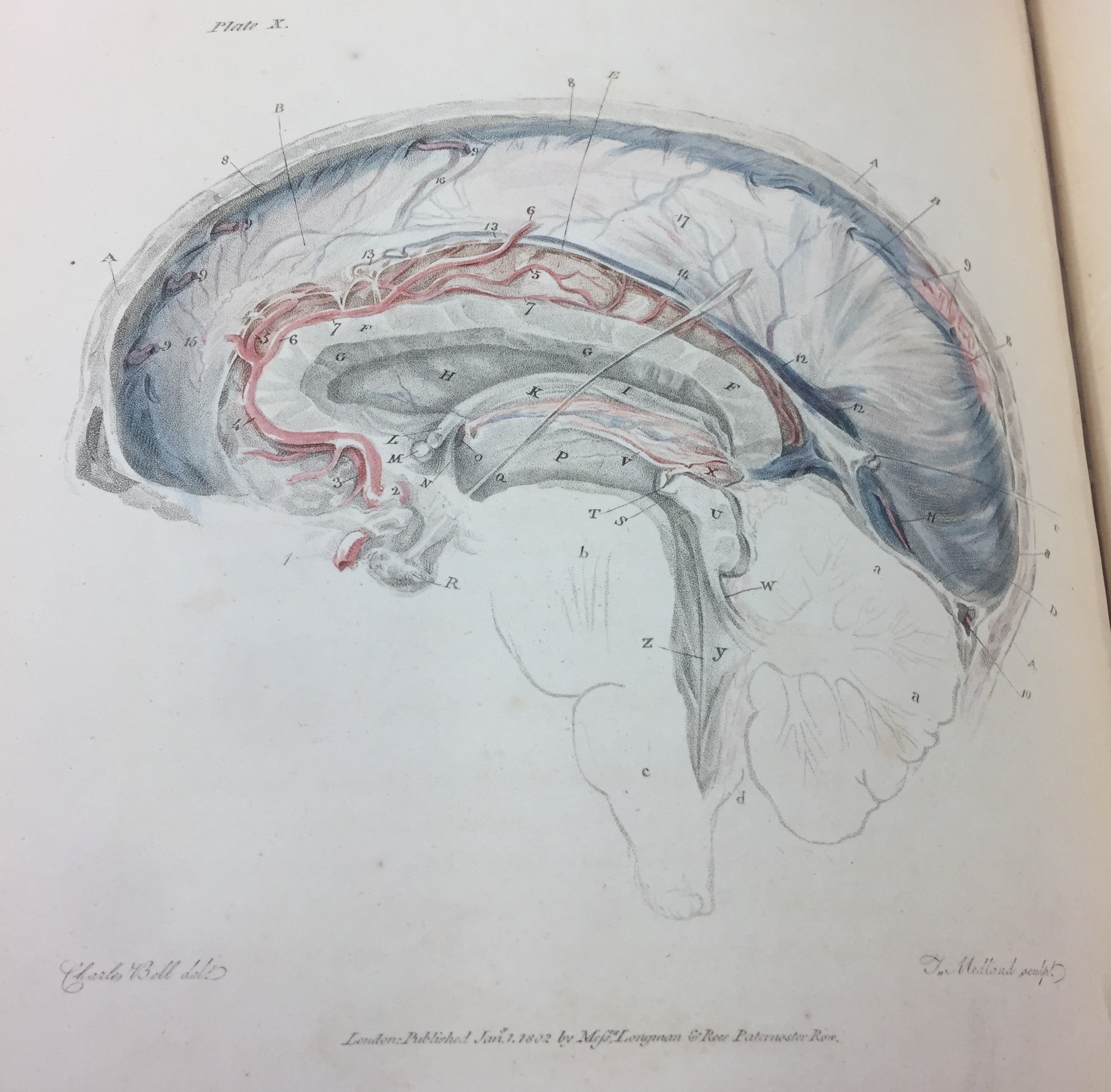

Charles Bell was a prolific author who combined his anatomical knowledge with his artistic eye to produce a number of highly detailed and beautifully illustrated books. In 1799, Bell published his first work "''A System of Dissections, explaining the Anatomy of the Human Body, the manner of displaying Parts and their Varieties in Disease''". His second work was the completion of his brother's four-volume set of "''The Anatomy of the Human Body"'' in 1803. In that same year, Bell published his three series of engravings titled "''Engravings of the Arteries"'', "''Engravings of the Brain''", and "''Engravings of the Nerves".'' These sets of engravings consisted of intricate and detailed anatomical diagrams accompanied with labels and a brief description of their functionality in the human body and were published as an educational tool for aspiring medical students. The "''Engravings of the Brain"'' are of particular importance for this marked Bell's first published attempt at fully elucidating the organization of the nervous system. In his introduction to the work, Bell comments on the ambiguous nature of the brain and its inner workings, a topic that would hold his interest for the remainder of his life.

In 1806, with his eye on a teaching post at the

Charles Bell was a prolific author who combined his anatomical knowledge with his artistic eye to produce a number of highly detailed and beautifully illustrated books. In 1799, Bell published his first work "''A System of Dissections, explaining the Anatomy of the Human Body, the manner of displaying Parts and their Varieties in Disease''". His second work was the completion of his brother's four-volume set of "''The Anatomy of the Human Body"'' in 1803. In that same year, Bell published his three series of engravings titled "''Engravings of the Arteries"'', "''Engravings of the Brain''", and "''Engravings of the Nerves".'' These sets of engravings consisted of intricate and detailed anatomical diagrams accompanied with labels and a brief description of their functionality in the human body and were published as an educational tool for aspiring medical students. The "''Engravings of the Brain"'' are of particular importance for this marked Bell's first published attempt at fully elucidating the organization of the nervous system. In his introduction to the work, Bell comments on the ambiguous nature of the brain and its inner workings, a topic that would hold his interest for the remainder of his life.

In 1806, with his eye on a teaching post at the  Despite this lukewarm response, Charles Bell continued to study the anatomy of the human brain and laid his focus upon the nerves connected to it. In 1821, Bell published the ''"On the Nerves: Giving an Account of some Experiments on Their Structure and Functions, Which Lead to a New Arrangement of the System"'' in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. This paper held Bell's most famous discovery, that the facial nerve or seventh cranial nerve is a nerve of muscular action. This was quite an important discovery because surgeons would often cut this nerve as an attempted cure for facial neuralgia, but this would often render the patient with a unilateral paralysis of the facial muscles, now known as Bell's Palsy. Due to this publication, Charles Bell is regarded as one of the first physicians to combine the scientific study of neuroanatomy with clinical practice.

Bell's studies on

Despite this lukewarm response, Charles Bell continued to study the anatomy of the human brain and laid his focus upon the nerves connected to it. In 1821, Bell published the ''"On the Nerves: Giving an Account of some Experiments on Their Structure and Functions, Which Lead to a New Arrangement of the System"'' in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. This paper held Bell's most famous discovery, that the facial nerve or seventh cranial nerve is a nerve of muscular action. This was quite an important discovery because surgeons would often cut this nerve as an attempted cure for facial neuralgia, but this would often render the patient with a unilateral paralysis of the facial muscles, now known as Bell's Palsy. Due to this publication, Charles Bell is regarded as one of the first physicians to combine the scientific study of neuroanatomy with clinical practice.

Bell's studies on

Sir Charles Bell engravings

–

Anatomia 1522–1867

' digital collection, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto * {{DEFAULTSORT:Bell, Charles 1774 births 1842 deaths 19th-century Scottish people Medical doctors from Edinburgh People educated at the Royal High School, Edinburgh Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Fellows of the Royal Society Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Philosophers of religion British neurologists British neuroscientists Scottish anatomists Scottish knights 19th-century Scottish medical doctors Scottish physiologists Scottish surgeons Academics of the University of Edinburgh Scottish medical writers Authors of the Bridgewater Treatises Committee members of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge

anatomist

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

, physiologist

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical a ...

, neurologist

Neurology (from el, νεῦρον (neûron), "string, nerve" and the suffix -logia, "study of") is the branch of medicine dealing with the diagnosis and treatment of all categories of conditions and disease involving the brain, the spinal c ...

, artist, and philosophical theologian

Philosophical theology is both a branch and form of theology in which philosophical methods are used in developing or analyzing theological concepts. It therefore includes natural theology as well as philosophical treatments of orthodox and heter ...

. He is noted for discovering the difference between sensory nerves

A sensory nerve, or afferent nerve, is a general anatomic term for a nerve which contains predominantly somatic afferent nerve fibers. Afferent nerve fibers in a sensory nerve carry sensory information toward the central nervous system (CNS) from ...

and motor nerves

A motor neuron (or motoneuron or efferent neuron) is a neuron whose cell body is located in the motor cortex, brainstem or the spinal cord, and whose axon (fiber) projects to the spinal cord or outside of the spinal cord to directly or indirectly ...

in the spinal cord. He is also noted for describing Bell's palsy

Bell's palsy is a type of facial paralysis that results in a temporary inability to control the facial muscles on the affected side of the face. In most cases, the weakness is temporary and significantly improves over weeks. Symptoms can vary fr ...

.

His three older brothers included Robert Bell (1757–1816) a Writer to the Signet

The Society of Writers to His Majesty's Signet is a private society of Scottish solicitors, dating back to 1594 and part of the College of Justice. Writers to the Signet originally had special privileges in relation to the drawing up of document ...

, John Bell (1763–1820), also a noted surgeon and writer; and the advocate George Joseph Bell

George Joseph Bell (26 March 177023 September 1843) was a Scottish advocate and legal scholar. From 1822 to 1843 he was Professor of Scots Law at the University of Edinburgh. He was succeeded by John Shank More.

Early life

George Bell was born ...

(1770–1843) who became a professor of law at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

and a principal clerk at the Court of Session

The Court of Session is the supreme civil court of Scotland and constitutes part of the College of Justice; the supreme criminal court of Scotland is the High Court of Justiciary. The Court of Session sits in Parliament House in Edinburgh ...

.

Early life and education

Charles Bell was born inEdinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

on 12 November 1774, as the fourth son of the Reverend William Bell, a clergyman of the Episcopal Church of Scotland

The Scottish Episcopal Church ( gd, Eaglais Easbaigeach na h-Alba; sco, Scots Episcopal(ian) Kirk) is the ecclesiastical province of the Anglican Communion in Scotland.

A continuation of the Church of Scotland as intended by King James VI, and ...

. Charles's father died in 1779 when he was five years old, and thus his mother had a profound influence on his early life, teaching him how to read and write. In addition to this, his mother also helped Charles's natural artistic ability by paying for his regular drawing and painting lessons from David Allan, a well-known Scottish painter. Charles Bell grew up in Edinburgh, and attended the prestigious High School

A secondary school describes an institution that provides secondary education and also usually includes the building where this takes place. Some secondary schools provide both '' lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) and ''upper seconda ...

(1784–88). Although he was not a particularly good student, Charles decided to follow in his brother John's footsteps and enter a career in medicine. In 1792, Charles Bell enrolled at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

and began assisting his brother John as a surgical apprentice. While at the university, Bell attended the lectures of Dugald Stewart

Dugald Stewart (; 22 November 175311 June 1828) was a Scottish philosopher and mathematician. Today regarded as one of the most important figures of the later Scottish Enlightenment, he was renowned as a populariser of the work of Francis Hut ...

on the subject of spiritual philosophy. These lectures had considerable impact on Bell, for some of Stewart's teachings can be traced in Bell's later works in a passage on his ''Treatise on the Hand''. In addition to classes on anatomy, Bell took a course on the art of drawing in order to refine his artistic skill. At the university he was also a member of the Royal Medical Society

The Royal Medical Society (RMS) is a society run by students at the University of Edinburgh Medical School, Scotland. It claims to be the oldest medical society in the United Kingdom although this claim is also made by the earlier London-based ...

as a student and spoke at the Society's centenary celebrations in 1837.

In 1798, Bell graduated from the University of Edinburgh and soon after was admitted to the Edinburgh College of Surgeons where he taught anatomy and operated at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary

The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, or RIE, often (but incorrectly) known as the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, or ERI, was established in 1729 and is the oldest voluntary hospital in Scotland. The new buildings of 1879 were claimed to be the largest v ...

. While developing his talents as a surgeon, Bell's interests forayed into a field combining anatomy and art. His inherent talent as an artist came to the fore when he helped his brother complete a four-volume work called ''The Anatomy of the Human Body''. Charles Bell completely wrote and illustrated volumes 3 and 4 in 1803, as well as publishing his own set of illustrations in a ''System of Dissections'' in 1798 and 1799. Furthermore, Bell used his clinical experience and artistic eye to develop the hobby of modelling interesting medical cases in wax. He proceeded to accumulate an extensive collection that he dubbed his Museum of Anatomy, some items of which can still be seen today at Surgeon's Hall

Surgeons' Hall in Edinburgh, Scotland, is the headquarters of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd). It houses the Surgeons' Hall Museum, and the library and archive of the RCSEd. The present Surgeons' Hall was designed by William ...

.

Charles Bell's stay in Edinburgh did not last long due to an infamous feud between John Bell and two faculty members at the University of Edinburgh: Alexander Monro Secundus

Alexander Monro of Craiglockhart and Cockburn (22 May 1733 – 2 October 1817) was a Scottish anatomist, physician and medical educator. He is typically known as or Junior to distinguish him as the second of three generations of physicians of ...

and John Gregory. John Gregory was the chairman of the Royal Infirmary and had declared that only six full-time surgical staff members would be appointed to work at the infirmary. The Bell brothers were not selected and thus barred from practicing medicine at the Royal Infirmary. Charles Bell, who was not directly involved in his brother's feuds, attempted to make a deal with the faculty of the University of Edinburgh by offering the university one hundred guineas and his Museum of Anatomy in exchange for allowing him to observe and sketch the operations performed at the Royal Infirmary, but this deal was rejected.

Professional career

In 1804, Charles Bell left forLondon

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

and in 1805 had established himself in the city by buying a house on Leicester Street. From this house Bell taught classes in anatomy and surgery for medical students, doctors, and artists. In 1809, Bell was among a number of civilian surgeons who volunteered to attend to the many thousands of ill and wounded soldiers who had retreated to Corunna, and 6 years later he again voluntarily attended to the ill and wounded in the aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo. Regrettably, of Bell's 12 amputation cases, only one man survived. In addition to the amputation surgeries, Bell was quite fascinated by musket-ball injuries and in 1814, he published a ''Dissertation on Gunshot Wounds''. A number of his illustrations of the wounds are displayed in the hall of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh.

In 1811, Charles Bell married Marion Shaw. Using money from his wife's dowry, Bell purchased a share of the Great Windmill Street School of Anatomy which had been founded by the anatomist William Hunter. Bell transferred his practice from his house to the Windmill Street School Bell ended up teaching students and conducting his own research until 1824. In 1813–14, he was appointed as a member of the London College of Surgeons and as a surgeon at the Middlesex Hospital.

In addition to his domestic pursuits, Bell also served as a military surgeon, making elaborate recordings of neurological injuries at the Royal Hospital Haslar

The Royal Hospital Haslar in Gosport, Hampshire, was one of several hospitals serving the local area. It was converted into retirement flats between 2018 and 2020. The hospital itself is a Grade II listed building.

History

Formation and oper ...

and famously documenting his experiences at Waterloo in 1815. For three consecutive days and nights, he operated on French soldiers in the Gens d'Armerie Hospital. The condition of the French soldiers was quite poor, and thus many of his patients died shortly after he operated on them. Dr Robert Knox

Robert Knox (4 September 1791 – 20 December 1862) was a Scottish anatomist and ethnologist best known for his involvement in the Burke and Hare murders. Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, Knox eventually partnered with anatomist and former teache ...

, who was one of Bell's surgical assistants at Brussels, was critical of Bell's surgical skills and commented rather negatively on Bell's surgical abilities; (the mortality rate of amputations carried out by Bell ran at about 90%).

Bell was instrumental in the creation of the Middlesex Hospital

Middlesex Hospital was a teaching hospital located in the Fitzrovia area of London, England. First opened as the Middlesex Infirmary in 1745 on Windmill Street, it was moved in 1757 to Mortimer Street where it remained until it was finally clos ...

Medical School, and became, in 1824, the first professor of Anatomy and Surgery of the College of Surgeons in London. In that same year Bell sold his collection of over 3,000 wax preparations to the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd) is a professional organisation of surgeons. The College has seven active faculties, covering a broad spectrum of surgical, dental, and other medical practices. Its main campus is located on ...

for £3000.

In 1829, the Windmill Street School of Anatomy was incorporated into the new King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of King George IV and the Duke of Wellington. In 1836, King's ...

. Bell was invited to be its first professor of physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical ...

, and helped establish the Medical School at the University of London, gave the inaugural address when it formally opened, and even helped contribute to the requirements of its certification program. Bell's stay at the Medical School did not last long and he resigned from his chair due to differences of opinion with the academic staff. For the next seven years, Bell gave clinical lectures at the Middlesex Hospital and in 1835 he accepted the position of the Chair of Surgery at the University of Edinburgh following the premature death of Prof John William Turner.

He was made a Knight of the Royal Guelphic Order

The Royal Guelphic Order (german: Königliche Guelphen-Orden), sometimes referred to as the Hanoverian Guelphic Order, is a Hanoverian order of chivalry instituted on 28 April 1815 by the Prince Regent (later King George IV). It takes its name ...

in 1833.

Bell died at Hallow Park near Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

in the Midlands, while travelling from Edinburgh to London, in 1842.

He is buried in Hallow

To hallow is "to make holy or sacred, to sanctify or consecrate, to venerate". The adjective form ''hallowed'', as used in ''The Lord's Prayer'', means holy, consecrated, sacred, or revered. The noun form ''hallow'', as used in ''Hallowtide'', ...

Churchyard near Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

.

Honours and awards

Bell was elected aFellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

Fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (FRSE) is an award granted to individuals that the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotland's national academy of science and letters, judged to be "eminently distinguished in their subject". This soci ...

on 8 June 1807, on the nomination of Robert Jameson

Robert Jameson

Robert Jameson FRS FRSE (11 July 1774 – 19 April 1854) was a Scottish naturalist and mineralogist.

As Regius Professor of Natural History at the University of Edinburgh for fifty years, developing his predecessor John ...

, William Wright and Thomas Macknight. He served as a Councillor of the RSE from 1836 to 1839.

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathematics ...

on 16 November 1826, and was awarded the Royal Society's gold medal for his numerous discoveries in science. Bell was knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

ed as a Knight of the Guelphic Order of Hanover in 1831 and, like Sir Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Ow ...

, was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences ( sv, Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien) is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special ...

.

Works

Charles Bell was a prolific author who combined his anatomical knowledge with his artistic eye to produce a number of highly detailed and beautifully illustrated books. In 1799, Bell published his first work "''A System of Dissections, explaining the Anatomy of the Human Body, the manner of displaying Parts and their Varieties in Disease''". His second work was the completion of his brother's four-volume set of "''The Anatomy of the Human Body"'' in 1803. In that same year, Bell published his three series of engravings titled "''Engravings of the Arteries"'', "''Engravings of the Brain''", and "''Engravings of the Nerves".'' These sets of engravings consisted of intricate and detailed anatomical diagrams accompanied with labels and a brief description of their functionality in the human body and were published as an educational tool for aspiring medical students. The "''Engravings of the Brain"'' are of particular importance for this marked Bell's first published attempt at fully elucidating the organization of the nervous system. In his introduction to the work, Bell comments on the ambiguous nature of the brain and its inner workings, a topic that would hold his interest for the remainder of his life.

In 1806, with his eye on a teaching post at the

Charles Bell was a prolific author who combined his anatomical knowledge with his artistic eye to produce a number of highly detailed and beautifully illustrated books. In 1799, Bell published his first work "''A System of Dissections, explaining the Anatomy of the Human Body, the manner of displaying Parts and their Varieties in Disease''". His second work was the completion of his brother's four-volume set of "''The Anatomy of the Human Body"'' in 1803. In that same year, Bell published his three series of engravings titled "''Engravings of the Arteries"'', "''Engravings of the Brain''", and "''Engravings of the Nerves".'' These sets of engravings consisted of intricate and detailed anatomical diagrams accompanied with labels and a brief description of their functionality in the human body and were published as an educational tool for aspiring medical students. The "''Engravings of the Brain"'' are of particular importance for this marked Bell's first published attempt at fully elucidating the organization of the nervous system. In his introduction to the work, Bell comments on the ambiguous nature of the brain and its inner workings, a topic that would hold his interest for the remainder of his life.

In 1806, with his eye on a teaching post at the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

, Bell published his ''Essays on The Anatomy of Expression in Painting'' (1806), later re-published as ''Essays on The Anatomy and Philosophy of Expression'' in 1824. In this work, Bell followed the principles of natural theology

Natural theology, once also termed physico-theology, is a type of theology that seeks to provide arguments for theological topics (such as the existence of a deity) based on reason and the discoveries of science.

This distinguishes it from ...

, asserting the existence of a uniquely human system of facial muscles

The facial muscles are a group of striated skeletal muscles supplied by the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) that, among other things, control facial expression. These muscles are also called mimetic muscles. They are only found in mammals, alth ...

in the service of a human species

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, an ...

with a unique relationship to the Creator, ideals which paralleled with those of William Paley

William Paley (July 174325 May 1805) was an English clergyman, Christian apologist, philosopher, and utilitarian. He is best known for his natural theology exposition of the teleological argument for the existence of God in his work ''Natural T ...

. After the failure of his application (Sir Thomas Lawrence

Sir Thomas Lawrence (13 April 1769 – 7 January 1830) was an English portrait painter and the fourth president of the Royal Academy. A child prodigy, he was born in Bristol and began drawing in Devizes, where his father was an innkeeper at t ...

, later President of the Royal Academy, described Bell as "lacking in temper, modesty and judgement"), Bell turned his attentions to the nervous system.

Bell published detailed studies of the nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its actions and sensory information by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body. The nervous system detects environmental changes th ...

in 1811, in his privately circulated book ''An Idea of a New Anatomy of the Brain''. In this book, Bell described his idea of the different nervous tracts connecting with different parts of brain and thus leading to different functionality. His experiments to investigate this consisted of cutting open the spinal cord of a rabbit and touching different columns of the cord. He found that an irritation of the anterior columns led to a convulsion of the muscles, while an irritation of the posterior columns had no visible effect. These experiments led Bell to declare that he was the first to distinguish between sensory and motor nerves. While this essay is considered by many to be the founding stone of clinical neurology, it was not well received by Bell's peers. His experimentation was criticized and the idea that he presented of the anterior and posterior roots being connected to the cerebrum and cerebellum respectively, was rejected. Furthermore, Bell's ''original'' essay of 1811 did not actually contain a clear description of motor and sensory nerve roots A nerve root (Latin: ''radix nervi'') is the initial segment of a nerve leaving the central nervous system. Nerve roots can be classified as:

*Cranial nerve roots: the initial or proximal segment of one of the twelve pairs of cranial nerves leaving ...

as Bell later claimed, and he seems to have issued subsequent incorrectly dated revisions with subtle textual alterations.

Despite this lukewarm response, Charles Bell continued to study the anatomy of the human brain and laid his focus upon the nerves connected to it. In 1821, Bell published the ''"On the Nerves: Giving an Account of some Experiments on Their Structure and Functions, Which Lead to a New Arrangement of the System"'' in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. This paper held Bell's most famous discovery, that the facial nerve or seventh cranial nerve is a nerve of muscular action. This was quite an important discovery because surgeons would often cut this nerve as an attempted cure for facial neuralgia, but this would often render the patient with a unilateral paralysis of the facial muscles, now known as Bell's Palsy. Due to this publication, Charles Bell is regarded as one of the first physicians to combine the scientific study of neuroanatomy with clinical practice.

Bell's studies on

Despite this lukewarm response, Charles Bell continued to study the anatomy of the human brain and laid his focus upon the nerves connected to it. In 1821, Bell published the ''"On the Nerves: Giving an Account of some Experiments on Their Structure and Functions, Which Lead to a New Arrangement of the System"'' in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. This paper held Bell's most famous discovery, that the facial nerve or seventh cranial nerve is a nerve of muscular action. This was quite an important discovery because surgeons would often cut this nerve as an attempted cure for facial neuralgia, but this would often render the patient with a unilateral paralysis of the facial muscles, now known as Bell's Palsy. Due to this publication, Charles Bell is regarded as one of the first physicians to combine the scientific study of neuroanatomy with clinical practice.

Bell's studies on emotional expression

An emotional expression is a behavior that communicates an emotional state or attitude. It can be verbal or nonverbal, and can occur with or without self-awareness. Emotional expressions include facial movements like smiling or scowling, simple b ...

played a catalytic role in the development of Darwin's considerations of the origins of human emotional life; and, while he rejected Bell's theological arguments, Darwin very much agreed with Bell's emphasis on the expressive role of the muscles of respiration

The muscles of respiration are the muscles that contribute to inhalation and exhalation, by aiding in the expansion and contraction of the thoracic cavity. The diaphragm and, to a lesser extent, the intercostal muscles drive respiration during q ...

. Darwin detailed these opinions in his ''The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

''The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals'' is Charles Darwin's third major work of evolutionary theory, following ''On the Origin of Species'' (1859) and '' The Descent of Man'' (1871). Initially intended as a chapter in ''The Desce ...

'' (1872), written with the active collaboration of the psychiatrist James Crichton-Browne

Sir James Crichton-Browne MD FRS FRSE (29 November 1840 – 31 January 1938) was a leading Scottish psychiatrist, neurologist and eugenicist. He is known for studies on the relationship of mental illness to brain injury and for the developmen ...

.

Bell was one of the first physicians to combine the scientific study of neuroanatomy with clinical practice. In 1821, he described in the trajectory of the facial nerve

The facial nerve, also known as the seventh cranial nerve, cranial nerve VII, or simply CN VII, is a cranial nerve that emerges from the pons of the brainstem, controls the muscles of facial expression, and functions in the conveyance of tas ...

and a disease, Bell's Palsy

Bell's palsy is a type of facial paralysis that results in a temporary inability to control the facial muscles on the affected side of the face. In most cases, the weakness is temporary and significantly improves over weeks. Symptoms can vary fr ...

which led to the unilateral paralysis of facial muscles, in one of the classics of neurology, a paper delivered to the Royal Society entitled ''On the Nerves: Giving an Account of some Experiments on Their Structure and Functions, Which Lead to a New Arrangement of the System.''

Bell also combined his many artistic, scientific, literary and teaching talents in a number of wax preparations and detailed anatomical and surgical illustrations, paintings and engravings in his several books on these subjects, such as in his book ''Illustrations of the Great Operations of Surgery: Trepan, Hernia, Amputation, Aneurism, and Lithotomy'' (1821). He wrote also the first treatise on notions of anatomy and physiology of facial expression

A facial expression is one or more motions or positions of the muscles beneath the skin of the face. According to one set of controversial theories, these movements convey the emotional state of an individual to observers. Facial expressions are a ...

for painters and illustrators, titled ''Essays on the Anatomy of Expression in Painting'' (1806).

In 1829, Francis Egerton, the eighth Earl of Bridgewater, died and in his will, he left a large sum of money to the President of the Royal Society of London. The will stipulated that the money was to be used to write, print, and publish one thousand copies of a work on the Power, Wisdom, and Goodness of God. The President of the Royal Society, Davies Gilbert appointed eight gentlemen to write separate treatises on the subject. In 1833, he published the fourth Bridgewater Treatise

The Bridgewater Treatises (1833–36) are a series of eight works that were written by leading scientific figures appointed by the President of the Royal Society in fulfilment of a bequest of £8000, made by Francis Henry Egerton, 8th Earl of Bridg ...

, ''The Hand: Its Mechanism and Vital Endowments as Evincing Design''. Charles Bell published four editions of ''The Hand''. In the first few chapters, Bell organizes his treatise as an early textbook of comparative anatomy. The book is full of pictures where Bell compares "hands" of different organisms ranging from human hands, chimpanzee paws, and fish feelers. After the first few chapters, Bell orients his treatise around the significance of the hand and its importance in its use in anatomy. He emphasizes that the hand is as important as the eye in the field of surgery and that it must be trained.

Legacy

A number of discoveries received his name: * Bell's (external respiratory) nerve: Thelong thoracic nerve

The long thoracic nerve (external respiratory nerve of Bell; posterior thoracic nerve) innervates the serratus anterior muscle.

Structure

The long thoracic nerve arises from the anterior rami of the C5, C6, and C7 cervical spinal nerve. Th ...

.

* Bell's palsy

Bell's palsy is a type of facial paralysis that results in a temporary inability to control the facial muscles on the affected side of the face. In most cases, the weakness is temporary and significantly improves over weeks. Symptoms can vary fr ...

: a unilateral idiopathic

An idiopathic disease is any disease with an unknown cause or mechanism of apparent wikt:spontaneous, spontaneous origin. From Ancient Greek, Greek ἴδιος ''idios'' "one's own" and πάθος ''pathos'' "suffering", ''idiopathy'' means approxi ...

paralysis

Paralysis (also known as plegia) is a loss of motor function in one or more muscles. Paralysis can also be accompanied by a loss of feeling (sensory loss) in the affected area if there is sensory damage. In the United States, roughly 1 in 50 ...

of facial muscles due to a lesion of the facial nerve

The facial nerve, also known as the seventh cranial nerve, cranial nerve VII, or simply CN VII, is a cranial nerve that emerges from the pons of the brainstem, controls the muscles of facial expression, and functions in the conveyance of tas ...

.

* Bell's phenomenon

Bell's phenomenon (also known as the palpebral oculogyric reflex) is a medical sign that allows observers to notice an upward and outward movement of the human eye, eye, when an attempt is made to close the eyes. The upward movement of the eye is ...

: A normal defense mechanism—upward and outward movement of the eye which occurs when an individual closes their eyes forcibly. It can be appreciated clinically in a patient with paralysis of the orbicularis oculi

The orbicularis oculi is a muscle in the face that closes the eyelids. It arises from the nasal part of the frontal bone, from the frontal process of the maxilla in front of the lacrimal groove, and from the anterior surface and borders of a short ...

(e.g. Guillain–Barré syndrome

Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) is a rapid-onset muscle weakness caused by the immune system damaging the peripheral nervous system. Typically, both sides of the body are involved, and the initial symptoms are changes in sensation or pain often ...

or Bell's palsy

Bell's palsy is a type of facial paralysis that results in a temporary inability to control the facial muscles on the affected side of the face. In most cases, the weakness is temporary and significantly improves over weeks. Symptoms can vary fr ...

), as the eyelid

An eyelid is a thin fold of skin that covers and protects an eye. The levator palpebrae superioris muscle retracts the eyelid, exposing the cornea to the outside, giving vision. This can be either voluntarily or involuntarily. The human eyel ...

remains elevated when the patient tries to close the eye.

* Bell's spasm: Involuntary twitching of the facial muscles

The facial muscles are a group of striated skeletal muscles supplied by the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) that, among other things, control facial expression. These muscles are also called mimetic muscles. They are only found in mammals, alth ...

.

* Bell-Magendie law or Bell's Law: States that the anterior branch of spinal nerve

A spinal nerve is a mixed nerve, which carries motor, sensory, and autonomic signals between the spinal cord and the body. In the human body there are 31 pairs of spinal nerves, one on each side of the vertebral column. These are grouped into th ...

roots contain only motor fibers and the posterior roots contain only sensory fibers., p. 92.

Charles Bell House, part of University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

, is used for teaching and research in surgery.

References

Further reading

* Bell, C., ''The Hand. Its Mechanism and Vital Endowments as Evincing Design''; Bridgewater Treatises, W. Pickering, 1833 (reissued byCambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by Henry VIII of England, King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press

A university press is an academic publishing hou ...

, 2009; )

* Berkowitz, Carin. ''Charles Bell and the Anatomy of Reform.'' Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015.

External links

Sir Charles Bell engravings

–

Anatomia 1522–1867

' digital collection, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto * {{DEFAULTSORT:Bell, Charles 1774 births 1842 deaths 19th-century Scottish people Medical doctors from Edinburgh People educated at the Royal High School, Edinburgh Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Fellows of the Royal Society Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Philosophers of religion British neurologists British neuroscientists Scottish anatomists Scottish knights 19th-century Scottish medical doctors Scottish physiologists Scottish surgeons Academics of the University of Edinburgh Scottish medical writers Authors of the Bridgewater Treatises Committee members of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge